The living room had an open firegrate and a coal burning oven. There was a sink and setpot for boiling the washing in (the setpot was filled with water then you started a fire underneath). Steam filled the room when it boiled. Washing was either hung across street in summer, or hung on pulleys and pulled up to the ceiling, or hung on lines stretched across the room in winter, or on a clothes-horse round the fire.

Many house shared lavatories. Middens in the same block contained ashes and waste. It was a hole in the wall with a wooden door. Each week the midden men came and backed a wagon pulled by a horse. One man climbed into the midden and shovelled out the refuse into the wagon.

Almost everyone kept an animal - cat,dog, pigeons, chickens or rabbits. Nearly every garden had a hut for the pets.

During WW2 the school allotments behind the Regal Cinema produced veg that was sold for the war effort.

Outside every house was a large hook fastened to a wall. Nettles, dandelions and burdock leaves were collected down the riverside and fields and hung there to dry. We used to make nettle beer and dandelion and burdock drinks.

On winter evenings rugs were made for Christmas out of strips of old coats, skirts etc. Hessian was stretched over a rug frame and a pattern drawn out.

There were few cars or buses. Trams clanked and gave out sparks. You heard them crackle on the overhead lines. Buses were used for outings to coast. Some were pulled by horses. Gigs and traps delivered goods and took people on business. Many people cycled. Deliveries were made by horse and cart.

The Education Department had a strict School Board Man, who came round if you were off school two days running. If you didn’t attend school you would be summoned to the Education Department before a board to be given a warning. You could then be sent to an Approved School for a while.

Almost everyone came to see a new baby and put a piece of silver in its hand.

We got our new clothes at Whitsuntide and paraded round relations (patent shoes, organza dresses, straw bonnets trimmed with flowers or fruit).

Many house shared lavatories. Middens in the same block contained ashes and waste. It was a hole in the wall with a wooden door. Each week the midden men came and backed a wagon pulled by a horse. One man climbed into the midden and shovelled out the refuse into the wagon.

Almost everyone kept an animal - cat,dog, pigeons, chickens or rabbits. Nearly every garden had a hut for the pets.

During WW2 the school allotments behind the Regal Cinema produced veg that was sold for the war effort.

Outside every house was a large hook fastened to a wall. Nettles, dandelions and burdock leaves were collected down the riverside and fields and hung there to dry. We used to make nettle beer and dandelion and burdock drinks.

On winter evenings rugs were made for Christmas out of strips of old coats, skirts etc. Hessian was stretched over a rug frame and a pattern drawn out.

There were few cars or buses. Trams clanked and gave out sparks. You heard them crackle on the overhead lines. Buses were used for outings to coast. Some were pulled by horses. Gigs and traps delivered goods and took people on business. Many people cycled. Deliveries were made by horse and cart.

The Education Department had a strict School Board Man, who came round if you were off school two days running. If you didn’t attend school you would be summoned to the Education Department before a board to be given a warning. You could then be sent to an Approved School for a while.

Almost everyone came to see a new baby and put a piece of silver in its hand.

We got our new clothes at Whitsuntide and paraded round relations (patent shoes, organza dresses, straw bonnets trimmed with flowers or fruit).

The lady kneeling on the pavement is busy 'donkey stoning' her doorstep - a traditional method of cleaning particular to Yorkshire and Lancashire. 'Donkey Stones' are scouring stones, made from a mixture of crushed sandstone, cement, bleach and water and originally named after the trade mark of one of the earliest producers, Roads of Manchester. Donkey stones were first used in the textile mills on greasy, slippy stone staircases to prevent accidents. Eventually, donkey stoning the doorstep became a source of pride amongst Northern housewives and stones were available in white, cream and brown for different decorative effects. Donkey stones could often be obtained from the rag and bone man in exchange for rags. The Manchester company of Eli Whalley and Co. was the last surviving manufacturer of donkey stones when it closed in 1979. The company's trademark was not a donkey, but a lion, chosen by Eli Whalley in reminiscence of his childhood visits to Belle Vue Zoo. The image of a lion was imprinted on every stone.

Image and text copyright of Leeds Library and Information Services

Bathtime: most houses had no bathroom so you hauled up the old tin bath from the cellar or you went to the slipper baths on Joseph Street

On May Day the May Queen was taken around the streets with her entourage on trimmed carts pulled by a horse who had ribbons plaited in mane and tail, and bells on the harness. Floats with kids dressed up. Prizes for the best one.

The Sunday School day out was to Methley where we played sport in the fields, and had tea, sandwiches and cake. Prizes were given for races and attendance at Sunday School.

Hunslet Feast came for about a week during the August bank holiday.

Tradespeople came to every street.

A tinker came about twice a year: “Kettles to mend”. He repaired kettles, buckets, pans , anything that had holes or needed handles fitting. He had a cart with a top on it from which hung pans, kettles, kitchen utensils.

The flower man had one arm. He came at weekends. You bought them to take to graves.

Fruit and veg was sold by Mr Delaney from a horse and cart.

The pot man came round selling seconds from a cart: earthenware baking bowls, basins, cups, plates, saucers, pie dishes and vases.

Winter was on its way when the pikelet girls came round with big wicker baskets, snow white caps and aprons.

The scissor grinder came on a bike. He ran our scissors and knives up a grinding wheel attached to the back wheel of bike (the back wheel lifted onto a stand and he pedalled).

During the Hunslet Carnival people toured streets dressed as fairies, frogs, clowns, jugglers, men on stilts.

The Tingalery Man had a brightly painted barrel organ, with a little monkey.

The Sunday School day out was to Methley where we played sport in the fields, and had tea, sandwiches and cake. Prizes were given for races and attendance at Sunday School.

Hunslet Feast came for about a week during the August bank holiday.

Tradespeople came to every street.

A tinker came about twice a year: “Kettles to mend”. He repaired kettles, buckets, pans , anything that had holes or needed handles fitting. He had a cart with a top on it from which hung pans, kettles, kitchen utensils.

The flower man had one arm. He came at weekends. You bought them to take to graves.

Fruit and veg was sold by Mr Delaney from a horse and cart.

The pot man came round selling seconds from a cart: earthenware baking bowls, basins, cups, plates, saucers, pie dishes and vases.

Winter was on its way when the pikelet girls came round with big wicker baskets, snow white caps and aprons.

The scissor grinder came on a bike. He ran our scissors and knives up a grinding wheel attached to the back wheel of bike (the back wheel lifted onto a stand and he pedalled).

During the Hunslet Carnival people toured streets dressed as fairies, frogs, clowns, jugglers, men on stilts.

The Tingalery Man had a brightly painted barrel organ, with a little monkey.

The lamplighter came evenings and early mornings with a long hook on his bike's crossbar. He pulled the chain hanging from gas lamps, and replaced broken mantles. He came again to turn them off in the morning. In later years a timeclock was put in so he was no longer needed, except to clean the glass and maintain lamps.

Mr. & Mrs. Frankland or Mr. Gibb delivered milk around the streets. It was carried in churns on a two wheel trap pulled by a pony. We took jugs or basins and bought a gill or pint measure that hung inside the churn.

The roundabout man came once a month. It was horse drawn. You got rides for clean empty jam jars or a penny.

The Knocker-up Man cost about a shilling a week. He came around 4 a.m. to wake miners and mill workers. Then he came every hour to wake factory, office and shop workers.

Visiting the doctor...or not

The doctor's surgery was a cold, miserable place. Long forms (benches) snaked round the walls or there were hard wooden chairs in rows. A lady pharmacist worked behind a wooden partition. She made up prescriptions that the doctor gave her when he’d seen you. You paid for them or had them put on your card. You also had to pay for the consultation. This was also added to your card. Money was collected on Fridays by a lady who called at your house and was called “the doctor woman”. You paid her 3d, 6d, or maybe a shilling. Many people couldn’t afford to go to the doctors so they made home-made remedies handed down in the family. Goose grease was rubbed on you for colds, as was wintergreen. Herbs were scalded, and honey or sugar added. We were wrapped in brown paper, rubbed with oils and had vests made of cotton wool which were pulled off a little each day.

Kids used to be given malt and cod-liver oil to build them up.

We had “Boots for Bairns” if you were poor. Your school sent you to the Town Hall where the wives of people in high office had collected clothes from friends and you were given them.

Carrie Stocks was born in 1932 and lived at Gill Place near Belinda Street

Mr. & Mrs. Frankland or Mr. Gibb delivered milk around the streets. It was carried in churns on a two wheel trap pulled by a pony. We took jugs or basins and bought a gill or pint measure that hung inside the churn.

The roundabout man came once a month. It was horse drawn. You got rides for clean empty jam jars or a penny.

The Knocker-up Man cost about a shilling a week. He came around 4 a.m. to wake miners and mill workers. Then he came every hour to wake factory, office and shop workers.

Visiting the doctor...or not

The doctor's surgery was a cold, miserable place. Long forms (benches) snaked round the walls or there were hard wooden chairs in rows. A lady pharmacist worked behind a wooden partition. She made up prescriptions that the doctor gave her when he’d seen you. You paid for them or had them put on your card. You also had to pay for the consultation. This was also added to your card. Money was collected on Fridays by a lady who called at your house and was called “the doctor woman”. You paid her 3d, 6d, or maybe a shilling. Many people couldn’t afford to go to the doctors so they made home-made remedies handed down in the family. Goose grease was rubbed on you for colds, as was wintergreen. Herbs were scalded, and honey or sugar added. We were wrapped in brown paper, rubbed with oils and had vests made of cotton wool which were pulled off a little each day.

Kids used to be given malt and cod-liver oil to build them up.

We had “Boots for Bairns” if you were poor. Your school sent you to the Town Hall where the wives of people in high office had collected clothes from friends and you were given them.

Carrie Stocks was born in 1932 and lived at Gill Place near Belinda Street

Black bright knees from playing taws (marbles) on the unmade streets in Bridges Place. Fireplaces black-leaded. Doorsteps and windowsills scrubbed and yellow scouring stone smoothed on, also known as donkey stone. The outside flags swept and scrubbed every week without fail, unless it rained then it would be done when it was dry. Windows were cleaned with vinegar and crumpled up newspapers.

The unmade roads in our street and Varley Square seemed to be made of very compressed black muck similar to tip hills residue. Nothing grew in it, not a single weed or blade of grass unless we put a little earth near the edge of the pavement, but whatever we put in soon died. There were a couple of fever grates, one near the edge of our pavements and one over the other side of the road. I suppose the fever grates were called that because of the old days. We were warned to keep away from them, and then in summer, water with disinfectant would be poured down (by nearly all the people in our street) so that they would not smell. These were for the torrential rain overflow when we had our powerful bouncing two and tanner raindrops on our heavy rainy days. I loved watching the rain bouncing on the pavement and better still going out and paddling in it. When it rained hard and in bed (thunderstorms I loved them) while safe and warm, falling asleep to the loud splashing and banging in the sky. The rain would come down in buckets, and torrents would wash the black sludge from the unmade road along with it. We made sure we didn’t play taws near them or they’d be gone forever. The best place was a small flat area of Cross Bridges Place, the bottom of our street, which wasn’t really a separate street, just a continuation of Bridges Place on the way to Varley Square.

We had a large gas lamp in our street, I remember at one time there used to be a lamplighter man come to light the lamp and to put it out again early in the morning as the dawn crept in. He had a long pole that had bits on the end to light the flame and a snuffer as well for putting it out. There were occasions I saw him come during the day with a little ladder on his bike so that he could clean the lamps and the glass. I suppose we became so used to the lamplighter that you did not notice him most of the time, well you wouldn’t early in the morning when you were small. I remember saying good morning to him when I started work in the mill and was up at 5 am. I had to get up that early or I wouldn’t have been awake enough to go to work. I had to make up the fire which had been banked up with damp slack to keep it going overnight.

The unmade roads in our street and Varley Square seemed to be made of very compressed black muck similar to tip hills residue. Nothing grew in it, not a single weed or blade of grass unless we put a little earth near the edge of the pavement, but whatever we put in soon died. There were a couple of fever grates, one near the edge of our pavements and one over the other side of the road. I suppose the fever grates were called that because of the old days. We were warned to keep away from them, and then in summer, water with disinfectant would be poured down (by nearly all the people in our street) so that they would not smell. These were for the torrential rain overflow when we had our powerful bouncing two and tanner raindrops on our heavy rainy days. I loved watching the rain bouncing on the pavement and better still going out and paddling in it. When it rained hard and in bed (thunderstorms I loved them) while safe and warm, falling asleep to the loud splashing and banging in the sky. The rain would come down in buckets, and torrents would wash the black sludge from the unmade road along with it. We made sure we didn’t play taws near them or they’d be gone forever. The best place was a small flat area of Cross Bridges Place, the bottom of our street, which wasn’t really a separate street, just a continuation of Bridges Place on the way to Varley Square.

We had a large gas lamp in our street, I remember at one time there used to be a lamplighter man come to light the lamp and to put it out again early in the morning as the dawn crept in. He had a long pole that had bits on the end to light the flame and a snuffer as well for putting it out. There were occasions I saw him come during the day with a little ladder on his bike so that he could clean the lamps and the glass. I suppose we became so used to the lamplighter that you did not notice him most of the time, well you wouldn’t early in the morning when you were small. I remember saying good morning to him when I started work in the mill and was up at 5 am. I had to get up that early or I wouldn’t have been awake enough to go to work. I had to make up the fire which had been banked up with damp slack to keep it going overnight.

I‘d give it a good poke and put a couple of lumps of coal on to get it flaming and put the big black immensely heavy cast iron kettle on to make tea.

My dinner consisted of a cold bacon sandwich or bread and jam. I couldn’t afford to buy dinner or sandwiches at work. The only thing I could afford to buy was a large mug of tea and on a rare occasion a big slab of apple pie that the canteen made fresh nearly every day. It was made in huge oblong tin trays and cut into decent sized squares. The apple pie cost 4d for a slice and I used to try and wait until the pie had been cut into several pieces as that way you would get a better piece with no crust around it so it had plenty of apples. Sometimes if I could afford it I would buy an extra piece to eat later with my mug of tea in the afternoon. You couldn’t go to the canteen in the afternoon except to bring the tea back. I think that was the best apple pie I remember as I was always ready to eat come dinner-time, working on a pair of mule gates took a lot of energy for a growing 15 year old.

I would read a book with my bacon or dripping sandwich and pint pot of tea. Reading would wake my brain up and then I was ready for anything even though I dreaded the mind-bending boredom of that mill and the smell, noise and mule gates and miserable chauvinistic men I had to work with. They resented the fact that as young woman I was very strong and could do most of the work including splicing the rope when it broke. Asa, who I worked with, taught me to splice a piece of rope in when the old one wore out, and for some reason seemed to be annoyed that I mastered the job. If I mended the rope when he wasn’t around I suppose he resented that I was young and a female, as the older men were very chauvinistic. Yorkshire men were, including the young ones!

Cariss Street, just a few steps away at the top our street and surrounding streets, was all cobblestones. The variety of cobblestones both in colour, size and shape was a source of wonder, as was the gas tar they were set in.

My dinner consisted of a cold bacon sandwich or bread and jam. I couldn’t afford to buy dinner or sandwiches at work. The only thing I could afford to buy was a large mug of tea and on a rare occasion a big slab of apple pie that the canteen made fresh nearly every day. It was made in huge oblong tin trays and cut into decent sized squares. The apple pie cost 4d for a slice and I used to try and wait until the pie had been cut into several pieces as that way you would get a better piece with no crust around it so it had plenty of apples. Sometimes if I could afford it I would buy an extra piece to eat later with my mug of tea in the afternoon. You couldn’t go to the canteen in the afternoon except to bring the tea back. I think that was the best apple pie I remember as I was always ready to eat come dinner-time, working on a pair of mule gates took a lot of energy for a growing 15 year old.

I would read a book with my bacon or dripping sandwich and pint pot of tea. Reading would wake my brain up and then I was ready for anything even though I dreaded the mind-bending boredom of that mill and the smell, noise and mule gates and miserable chauvinistic men I had to work with. They resented the fact that as young woman I was very strong and could do most of the work including splicing the rope when it broke. Asa, who I worked with, taught me to splice a piece of rope in when the old one wore out, and for some reason seemed to be annoyed that I mastered the job. If I mended the rope when he wasn’t around I suppose he resented that I was young and a female, as the older men were very chauvinistic. Yorkshire men were, including the young ones!

Cariss Street, just a few steps away at the top our street and surrounding streets, was all cobblestones. The variety of cobblestones both in colour, size and shape was a source of wonder, as was the gas tar they were set in.

Some cobblestones were a lovely golden colour; there was beige, brown, light tan and darker, and various shades of grey. They had a lot of different shapes and sizes.

Mostly they were of smooth stone, some with tops rounded like a loaf that had risen well. When I was 15 years old and riding my bike to work you had to work out the best way over these humps. Sometimes you rode in a zigzag to avoid the largest and highest cobbles or you would come off the bike with a bang. There were streets that had fairly even cobbles. Cariss Street had a multitude of shapes, colours and sizes. I must have spent hours studying them trying to find an identical cobblestone and whenever I thought I’d found it I realised that it had something slightly different, maybe a corner or a blemish.

Come the summer, if it was very hot, the tar would melt and you had to be so careful as if it got on your socks shoes or clothes you’d never get it off again. We used to prise little bits out and roll them into balls like small marbles so we could play at taws. The smell of the gas tar was very strong and was a bit hard to get rid of the black stain on your fingers and the smell. Once in a blue moon Gas Tar men would come with their enormous black boiler to melt the tar, shovelling coal underneath into the burner to stoke the fire that melted the tar. These Gas Tar machines and their fumes were supposed to have healing properties. Mothers would bring their children who were chesty and hold them over it; they really believed the fumes would help bronchitis and other chest complaints (wishful thinking). How do I know this? Because I always suffered from bronchitis. I was possibly six or seven, I remember being terrified as my mother asked one of the men to hold me up to the fumes and I know I kicked and bobbed and carried on until they put me down. I firmly believed I was going to be put in or falling into the bubbling tar. I was never able to scream but I could yell very loudly and I did as long and loudly as I could and cried until I was hoarse. Mum tried to explain but I was convinced I would have fallen in. I have never forgotten that horrible experience because of old wives tales and my mam, usually quite sceptical normally, thought she would give it a try, as I had a lot of bronchitis and maybe desperate to try anything, as the doctors were not much help.

Living in a dirty industrial city and the local factories and chemical works nearby I suppose it’s a wonder we survived. You only had to see the blackness of the bricks on the houses to see the filth and soot for many, many years and were still there in the 1950s when I escaped.

Audrey Ann King (nee Naylor) was born in 1935 and lived in Bridges Place, off Church Street.

Mostly they were of smooth stone, some with tops rounded like a loaf that had risen well. When I was 15 years old and riding my bike to work you had to work out the best way over these humps. Sometimes you rode in a zigzag to avoid the largest and highest cobbles or you would come off the bike with a bang. There were streets that had fairly even cobbles. Cariss Street had a multitude of shapes, colours and sizes. I must have spent hours studying them trying to find an identical cobblestone and whenever I thought I’d found it I realised that it had something slightly different, maybe a corner or a blemish.

Come the summer, if it was very hot, the tar would melt and you had to be so careful as if it got on your socks shoes or clothes you’d never get it off again. We used to prise little bits out and roll them into balls like small marbles so we could play at taws. The smell of the gas tar was very strong and was a bit hard to get rid of the black stain on your fingers and the smell. Once in a blue moon Gas Tar men would come with their enormous black boiler to melt the tar, shovelling coal underneath into the burner to stoke the fire that melted the tar. These Gas Tar machines and their fumes were supposed to have healing properties. Mothers would bring their children who were chesty and hold them over it; they really believed the fumes would help bronchitis and other chest complaints (wishful thinking). How do I know this? Because I always suffered from bronchitis. I was possibly six or seven, I remember being terrified as my mother asked one of the men to hold me up to the fumes and I know I kicked and bobbed and carried on until they put me down. I firmly believed I was going to be put in or falling into the bubbling tar. I was never able to scream but I could yell very loudly and I did as long and loudly as I could and cried until I was hoarse. Mum tried to explain but I was convinced I would have fallen in. I have never forgotten that horrible experience because of old wives tales and my mam, usually quite sceptical normally, thought she would give it a try, as I had a lot of bronchitis and maybe desperate to try anything, as the doctors were not much help.

Living in a dirty industrial city and the local factories and chemical works nearby I suppose it’s a wonder we survived. You only had to see the blackness of the bricks on the houses to see the filth and soot for many, many years and were still there in the 1950s when I escaped.

Audrey Ann King (nee Naylor) was born in 1935 and lived in Bridges Place, off Church Street.

Children in my day got toys or sports equipment only at Christmas or on their birthdays. They didn't get anything in between other than comics, but they did get comics every week and it was a big thing, everyone read them and swapped them. You generally got two a week out of your pocket money, which in 1954 was a shilling a week for me - five pence today, and a comic would be one penny in today's money. If you were under about 12 you got the Beano or Dandy or Topper,which had picture cartoon strips, and if older you may have got the Rover, Wizard or Hotspur which were full of adventure stories and working class boys who grew up to be world-famous cricketers or footballers.

Geoff Tebbutt, who now lives in France, was born in 1942 in the Peppers

Geoff Tebbutt, who now lives in France, was born in 1942 in the Peppers

Woodville Place,Wodhouse Hill,1966

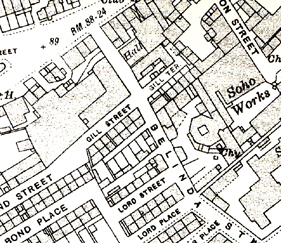

Gill Place

Church St

Click here for a wider map

Church St

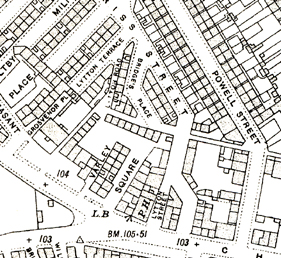

Bridges Place

Click here for a wider map

Home and around (1)

The Daily life section is a treasure-trove of Hunslet memories. Click on a subject in the drop-down box on the right to read about life in the home, industries, schools, churches and chapels, entertainment, games and sport, and pubs and clubs.

You are here: Home > Daily Life > Home and around (1)

In 1947 we were living in the yard behind the Gardeners Arms pub on Beza Street.

I attended Hunslet National school, Church Street but the snow was so deep it was impossible to get out of the yard to attend. I was aged nine at the time. I played on Station Moor which was the grass area between Beza Street and Hunslet Station. From there we moved to Milner Place. The toilet was down the street and it was not nice when you went down there and discovered that the next door neighbour was already in the toilet; you had to return home and hope that they would not be too long. The toilet seat was a double, and the usual lit candle was installed during freezing weather. There was no dustbins; we used what was known as a midden. This was just a hole in the wall behind the toilets.

In 1952 I was a pupil at Hunslet National School on Church Street. Mr Dunn was the headmaster and the teachers I remember were Mr Hobson, Mr Podmore, Mr Penny and Mr Jones. Sometimes at assembly Mr Dunn would play his violin, he enjoyed himself but we just cringed.

The school clinic was situated in the ginnel that ran from Anchor Street to Powell Street and the dentist there used ether to knock us out, it was horrible stuff, you were certain to be violently sick when you came round. The nit nurse there was also kept rather busy.

I remember the shops at the Balm Road end of Church Street in the early 1950s. Beethams, pawnbrokers, Pease newsagent and tobacconists, Sinclairs, leather goods, then there was the popular pub the Anchor (a Tetleys house), and at the end was Sam Sweetings, electricial goods. I purchased my first ever gramophone player there, it was a wind up one.

I attended Hunslet National school, Church Street but the snow was so deep it was impossible to get out of the yard to attend. I was aged nine at the time. I played on Station Moor which was the grass area between Beza Street and Hunslet Station. From there we moved to Milner Place. The toilet was down the street and it was not nice when you went down there and discovered that the next door neighbour was already in the toilet; you had to return home and hope that they would not be too long. The toilet seat was a double, and the usual lit candle was installed during freezing weather. There was no dustbins; we used what was known as a midden. This was just a hole in the wall behind the toilets.

In 1952 I was a pupil at Hunslet National School on Church Street. Mr Dunn was the headmaster and the teachers I remember were Mr Hobson, Mr Podmore, Mr Penny and Mr Jones. Sometimes at assembly Mr Dunn would play his violin, he enjoyed himself but we just cringed.

The school clinic was situated in the ginnel that ran from Anchor Street to Powell Street and the dentist there used ether to knock us out, it was horrible stuff, you were certain to be violently sick when you came round. The nit nurse there was also kept rather busy.

I remember the shops at the Balm Road end of Church Street in the early 1950s. Beethams, pawnbrokers, Pease newsagent and tobacconists, Sinclairs, leather goods, then there was the popular pub the Anchor (a Tetleys house), and at the end was Sam Sweetings, electricial goods. I purchased my first ever gramophone player there, it was a wind up one.

Daily Life

The best tram ride was from Middleton down to Hunslet Moor, especially if the journey was at night when it was dark. The tram only had one small headlight and would hurtle down through Middleton Woods at great speed; this could be quite a scary ride. The tram would then continue over the moor and go past the old man's shelter and the horse trough. The trams were very much a part of old Hunslet.

When I married in 1959 our first house was in Arthington Place, Hunslet Carr. At the top of the street was the lake (no water) with its bowling greens. On Arthington Avenue there was a Co-op which later closed and became a painting and decorating shop. There was also a butchers and a grocers shop. There was a variety of shops on Balm Road; one of these was Dawes the baker. Their bread and buns etc were very nice. On the opposite side of the road was the CWS brush works. The local pubs were the Engine and the Prospect. On Balm Road near the bridge was Balm Mill; part of the mill was at this time used as a fish cannery. There was a handy short cut from Balm Road to the Arthingtons: this started between the bridge and the mill and continued along the side of Balm Beck and you then arrived at the bottom of the Arthingtons. This was a neighbourly area at this time, everybody just about knew everybody else. They were happy days.

When I married in 1959 our first house was in Arthington Place, Hunslet Carr. At the top of the street was the lake (no water) with its bowling greens. On Arthington Avenue there was a Co-op which later closed and became a painting and decorating shop. There was also a butchers and a grocers shop. There was a variety of shops on Balm Road; one of these was Dawes the baker. Their bread and buns etc were very nice. On the opposite side of the road was the CWS brush works. The local pubs were the Engine and the Prospect. On Balm Road near the bridge was Balm Mill; part of the mill was at this time used as a fish cannery. There was a handy short cut from Balm Road to the Arthingtons: this started between the bridge and the mill and continued along the side of Balm Beck and you then arrived at the bottom of the Arthingtons. This was a neighbourly area at this time, everybody just about knew everybody else. They were happy days.

On the opposite side of the junction with Balm Road was the Laporte Chemical Works. Quite often there would be a layer of a yellow powdery substance on the pavement and roads in the area; this was an emission from Laportes, that certainly would not be allowed to happen now.

I supported Hunslet RLFC from an early age. When I began to support the team I stood out in the open at Mother Bensons end.

After I had endured quite a few soakings from the rain I upgraded to the stands and a seat. I saw some great players: Ginger Burnell, Freddie Williamson, Ted Carroll etc.

I also visited Parkside Greyhound Stadium, situated at the bottom of Old Run Road, not far from the Engine Public House. The stadium was what is known as a flapping track, meaning it was not licenced by the NGRC, the greyhound official body. The stadium was rather ramshackle but it attracted a good crowd most nights. When the track eventually closed down it was really missed by many of the locals.

When we decided to go into town (Leeds) we would go to the tram stop at the bottom of Anchor Street. The tram would have come from Belle Isle and would continue its journey via Waterloo Road, Swan Junction, Hunslet Road, Hunslet Lane, then over Leeds Bridge turn left into Swinegate where the tram depot was; this later became the Queens Hall.

I supported Hunslet RLFC from an early age. When I began to support the team I stood out in the open at Mother Bensons end.

After I had endured quite a few soakings from the rain I upgraded to the stands and a seat. I saw some great players: Ginger Burnell, Freddie Williamson, Ted Carroll etc.

I also visited Parkside Greyhound Stadium, situated at the bottom of Old Run Road, not far from the Engine Public House. The stadium was what is known as a flapping track, meaning it was not licenced by the NGRC, the greyhound official body. The stadium was rather ramshackle but it attracted a good crowd most nights. When the track eventually closed down it was really missed by many of the locals.

When we decided to go into town (Leeds) we would go to the tram stop at the bottom of Anchor Street. The tram would have come from Belle Isle and would continue its journey via Waterloo Road, Swan Junction, Hunslet Road, Hunslet Lane, then over Leeds Bridge turn left into Swinegate where the tram depot was; this later became the Queens Hall.

The Gardeners Arms

The Anchor and shops

Parkside from Mother Benson's end

Keith Murray was born in 1938

During some summers there would be a fortnight's heatwave. The humid heat in those houses was appalling and people would bring their chairs out into the street and sit there. It also changed people's personalities: the effect of being constantly outdoors made them behave like Italians, talking expansively and gesticulating.

"Collectors" tramped or biked round Hunslet, gathering say 3d a week from families to pay doctors' bills.

John Livingstone was an assistant priest at Hunslet Parish Church from 1955-60. He now lives in France.

"Collectors" tramped or biked round Hunslet, gathering say 3d a week from families to pay doctors' bills.

John Livingstone was an assistant priest at Hunslet Parish Church from 1955-60. He now lives in France.